Taniguchi Blossoms

March 22, 2012 § 5 Comments

This is my contribution to March 2012’s Manga Moveable Feast. The MMF is (in Johanna Draper Carlson’s words) “a virtual book club in which anyone can participate,” and where manga bloggers make a particular creator or book the subject of a flurry of posts over the space of a single week. March’s MMF focuses on the great Jiro Taniguchi—oddly appropriate, given that Taniguchi was the only manga artist to collaborate with the recently-deceased Moebius (on Icaro [2001]).

1.

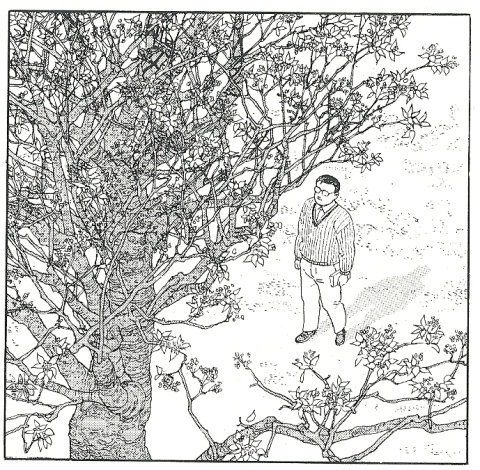

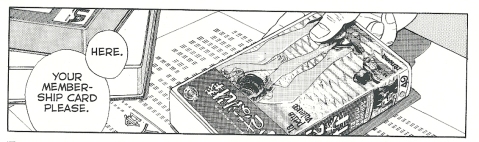

“A Blanket of Cherry Blossom” is probably my favorite story in Taniguchi’s The Walking Man (1992; translated by Fanfare / Ponent Mon in 2004). “Blossom” begins with the Walking Man—the unnamed hero whose strolls comprise the book’s Zen-like adventures—renting a video and, while walking home, coming upon an expansive courtyard with an old, beautiful cherry tree. He feels the tree’s bark, he buries his hand in the blossoms the tree is shedding upon the ground, and he lies down by the tree’s trunk and stares up at its branches. Then a beautiful woman hovers into his field of vision. She says to the Walking Man, “You’re in my place!”

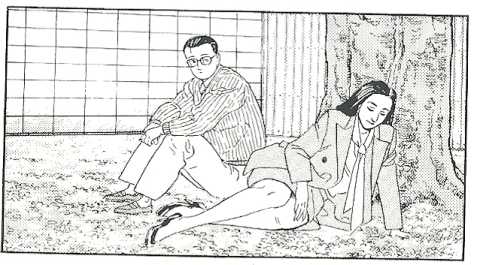

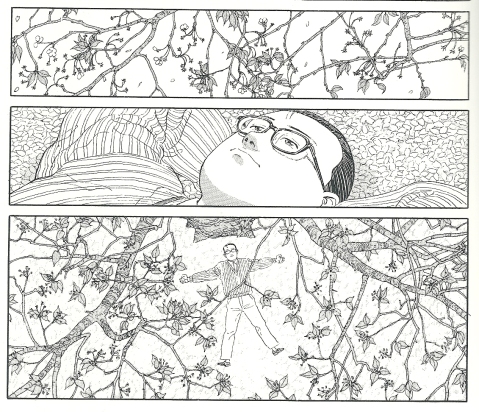

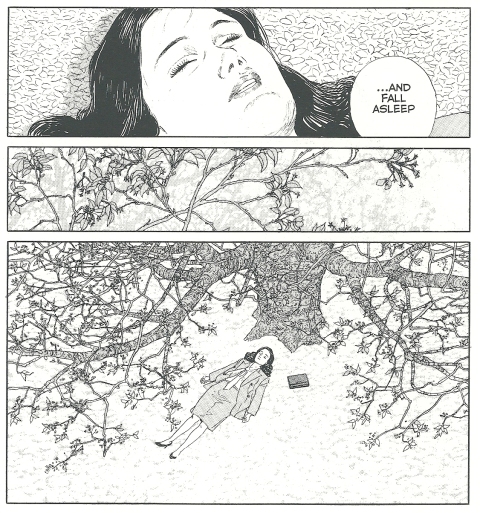

Like the Walking Man, the woman rubs her hand against the tree bark and touches blossoms. She sits with her back against the tree, and then the story seems to skip slightly forward in time. On a page turn, we see the woman telling the Walking Man about her relationship to the tree: “I moved away…before it flowered. I just wanted to see it one more time.” She too lies down by the tree trunk. She talks about a childhood when she’d “often lie here…and fall asleep,” and then she closes her eyes and dozes.

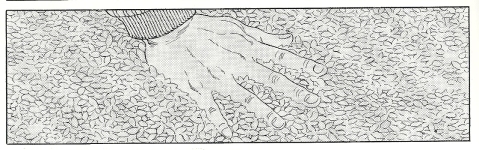

On the final page of the story, the Walking Man returns home, only to realize (with the help of his wife) that he’d left the rented video back at the cherry tree. He retrieves the video. The woman is gone. He immerses his hand in the blanket of cherry blossoms covering the ground again.

2.

The movie the Walking Man rents is La Petite Voleuse (The Little Thief, 1988), directed by Claude Miller and based on an unfilmed story by François Truffaut (who died in 1984 at the age of 52). In Voleuse, Charlotte Gainsbourg plays Janine, a 16-year-old kleptomaniac trapped in a particularly cruel 1950s French school and an unstable home life. (Both her mother and father have abandoned Janine, and she is raised by an aunt and uncle.) Janine runs away from home, dabbles in crime, loses her virginity; the film plays like a version of Truffaut’s Les quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows, 1959), but this time with an aimless, damaged young female protagonist.

In Taniguchi’s “Blossoms,” the woman has deeply nostalgic memories of the tree. Did it provide her with what little stability and beauty she remembers in her own childhood? By referencing La Petite Voleuse at the beginning of his tale, does Taniguchi hint that the woman’s past is as troubled as Janine’s?

3.

The woman is glamorous and impeccably dressed. The Walking Man is silent as she speaks of her childhood and her love for the tree. He stares at her, however, and his glances are sometimes secretive, as in the panel where he looks at her backside (with a slightly guilty expression on his face) as the woman leans away from him.

As she lays on the ground and naps, the Walking Man remains by her side and an unknown amount of story time passes—during which the Walking Man is free to look at her beautiful body and face while she sleeps.

The central conceit of Taniguchi’s Walking Man is that our anonymous protagonist is a sensitive observer: he sees the joyous and poignant aspects of everyday life that the rest of us habitually ignore. Yet is his gaze always that of a detached, innocent seer? In “Blossom,” could his gaze be sexual, fueling dreams of intimacy with the beautiful woman (as opposed to his wife, who makes an appearance in the story and who Taniguchi always draws as a cute, down-to-earth and decidedly non-glamorous gamin figure)? At the end of “Blossom,” night falls as the Walking Man returns to the tree to retrieve the Voleuse video. When he places his hand on the ground again, into the blossoms, and onto the spot where the woman was sleeping, is he trying to touch the warmth of her body, the ghost of her presence?

4.

Here are the two close-ups of the Walking Man touching the ground and the blossoms:

The same gesture, but with variations: the first touch occurs during the day, and the second at night, and the hands are reverse-images of each other. This aesthetic strategy—repetition with variation—dominates the structure of Taniguchi’s “Blossom.” Both the Walking Man and the Beautiful Woman derive sensual pleasure from touching cherry blossoms; both recline under the tree, and as each reclines we see their faces in close-up. Further, both are portrayed in aerial shots as they lie on the ground, their bodies reclining in opposite directions. Repetition with variation.

“Blossom” is also bookended by the Walking Man performing the same act—picking up the video—but in different locales (the video store, the tree).

How much does repetition with variation shape Taniguchi’s career as a whole? The Walking Man stories are all variants on a single formula—the observer sensitively perceives and responds to the quotidian world around him—while A Distant Neighborhood (1998/2009) places the possibility of “do-overs,” of repetition with variation, at the center of its plot. Why is Taniguchi so interested in stories that replace forward momentum with recurrence, cyclical organization, incremental change, and echoes of the past in the narrative present?

5.

Taniguchi’s art is the antithesis of expressionism: he represents the world with as much objectivity as he can, and the results are both breathtaking (in its cascade of details) and a little abstract, a little detached, not unlike the Walking Man himself. When Taniguchi draws the branches of a cherry tree, it’s a triumph of accretive detail, a network of overlapping forms rather than an emotional celebration of plant life. (A Taniguchi tree is not a Craig Thompson tree.) Taniguchi’s art is cool, more like mapmaking than passionate storytelling.

Another story in The Walking Man, “A Nice Hot Bath,” begins with the eponymous character reading Jonathan Lipman’s book about Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs for two business buildings in Racine, Wisconsin. Is Taniguchi acknowledging here the inspiration he takes from blueprints, from architecture?

6.

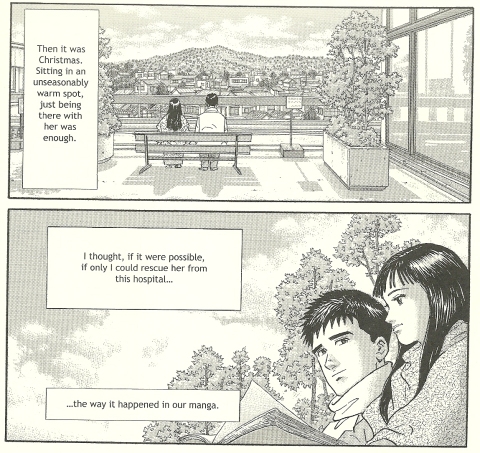

Why do I love Taniguchi’s manga so much? Is it the contradiction, the frisson, between the perfection of his diagrammatic art and the repressed but percolating emotions of the characters that inhabit his settings? At the end of A Zoo in Winter (2008/2011), the young couple—one of whom is an autobiographical stand-in for Taniguchi himself—read the manga they’ve written together, while sitting in a cozy spot at the hospital that provides an extraordinary view of the nearby village. They’re swathed in beauty, but this beauty—like all beauty—will pass. They both know the girl is going to die, and they know they’ll never consummate their love, yet they smile, in a perfect exhibition of mono no aware.

How painful is a life of missed opportunities? How painful are long-term losses and regrets? Do occasional moments of magnificence—such as the blissful visions that the Walking Man extricates from even the dingiest neighborhoods—justify or redeem suffering? Isn’t life disappointing? Or is it coherent and transcendent, if we only had eyes to see?

[…] Fischer has written a must-read piece on the opening story of The Walking Man, “A Blanket of Cherry Blossom”. His essay is meditative and thoughtful with […]

This is a beautiful piece, Craig!

[…] up the latest contributions to the Jiro Taniguchi Manga Movable Feast. Among the highlights is a thought-provoking essay by Craig Fischer on The Walking Man. “Taniguchi’s art is the antithesis of expressionism: he represents the […]

I think much of taniguchis work would seem warmer if it wasn’t on that darn glossy paper! I’m not against the schematic objectivity of his illustrations by any means, because his characters and locations have so much heart — but that paperstock totally retrenches that intimacy for me. Perhaps because I imagine it to be so much different than the paper he was drawing on?

In a recent interview, Fanfane / Ponent Mon publisher Stephen Robson mentioned that he’ll be reprinting THE WALKING MAN “in due time,” and encourages readers to contact him with suggestions. Maybe we should bug him about different paper for the reprint edition…?